Mission

Empowering the community through education and installation of renewable energy solutions

Vision

Building a better word together where people are the focus and renewable energy is the solution

Values

Integrity, Knowledge, Service, Compassion

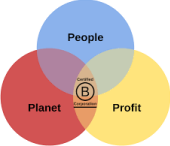

Patriot Power Company aspires to become a Certified Benefit Corporation

An aspiring Benefit (B) Corporation means we are seeking certification to be legally bound and proud to meet high standards of verified performance in benefiting society, being accountable and transparent with employee benefits, charitable giving, supply chain practices, and input materials.

We are currently a veteran preference and equal opportunity employer actively supporting non-profits who provide equine-facilitated therapy to veterans and trauma survivors.

“It’s not just about our business, it’s about the benefit we create.”

– Michael Lokey, CEO Patriot Power Company

To learn more about Equine-facilitated therapy, please see the article “I wouldn’t be alive without it’: wild mustangs and veterans find healing together” by The Guardian at the rear of this document.

Patriot Power Company

Benefactors and Partners

Operation Wild Horse

Operation Wild Horse

(OWH) a program of Veterans R&R 501(c)3 provides a safe community where Veterans, Active-Duty Military, and Families can build a significant Mustang/human bond that allows barriers to fall, communication to enhance, and trust to form.

Mission Mustang

Mission Mustang

The U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and EquiCenter, partnered to develop a national model called Mission Mustang™. This program’s purpose is to document the process of gentling and training wild horses and burros for eventual placement into loving homes, including integration into other therapeutic equestrian programs designed to improve the health and wellbeing of veterans suffering from Post Traumatic Stress (PTS), Traumatic Brain Injuries, and other physical and mental wounds.

Forget Me Not Home for Peculiar Animals is a 501(c)3 organization. Our mission is to rescue unwanted animals from all walks of life and provide them a safe and loving refuge either at our 20 acre facility in Wellington, Florida or adopted to forever homes. In addition, we work with children and teens to facilitate a greater understanding of all species in the world and encourage empathy.

Through these program areas, the Texas Veterans Commission provides excellent service so that each veteran receives every benefit that they deserve. As a veteran works with our counselors, the quality of life for that veteran and their family significantly increases. Today, Texas is leading the country by making sure each veteran is represented and cared for. The people of Texas have sent a clear message that the sacrifices made by veterans and their families are deeply appreciated, and that there is an agency that will stand by them and take care of them: the Texas Veterans Commission.

Patriot Power Company’s Benefits Inspiration

A wild mustang named Beacon at the Equicenter in Honeoye Falls, NY. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

At a stable in rural New York, traumatized soldiers and horses teach each other to leave the past behind.

by Jess McHugh

Mon 9 Aug 2021 05.00 EDT

Sierra doesn’t trust humans. She is quick to jump back in fear at loud noises or sudden movements. A bright sorrel color – much like the red rocks of the desert canyons in her home state of Nevada – Sierra grew up as one of the tens of thousands of wild horses that roam 10 western states in the US.

Captured from Nevada and shipped to the opposite side of the country by the Bureau of Land Management, she has never experienced human contact. Her mane is matted down, as no one has been able to groom her since she first arrived here in rural Monroe County, New York, 10 months ago.

Phil Wytrwa stands at the center of the small horse ring, bounded by a locked, 6-foot high metal enclosure. He moves deliberately, walking to one side of the horse and then to the other. He’s compact under a blue flannel shirt, a baseball hat with the word “veteran” on it pulled low over his head. The horse watches him but doesn’t back away. Minutes go by with only the sound of their feet in the sandy ring and the horse’s breathing – or snorting when the wind rustles the canvas ceiling and frightens her

Phil Wytrwa spends time with a mustang named Tango. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

A Veteran’s Story

A veteran of the war in Afghanistan, Wytrwa, 30, knows better than most what it means to feel hyper-vigilant and distrustful. He’s attuned to those same feelings in Sierra. At one point, he stops and stands motionless, taking a deep breath in and out. His shoulders drop. Sierra’s jaw unclenches. She’ll even let him stroke her neck

“I can feel her breathing. I can feel the vibration of it. I can feel that she’s scared. I can see the little things that she does. I can really just feel her,” he later explained.

Once he has her attention, his left arm points the direction and his right arm – tattooed with a distorted compass and the words “let’s get lost” – traces circles in the air to show her how fast to go. She trots, even breaks into a canter. She’s new to this, so the canter might last only a few seconds, but after she stops, she turns back to Wytrwa as if to say: “What’s next?”

We are at EquiCenter, a therapeutic equestrian facility where, under the supervision of a horse trainer, Wytrwa is one of 16 veterans who have sought reprieve from post traumatic stress among one of the most unpredictable animals: wild mustangs. EquiCenter runs a program that matches veterans with mustangs to train. Training the horses serves as a kind of therapy, helping veterans rebuild their own confidence, focus and sense of purpose.

Wytrwa described a life transformed by this work. When he returned from Afghanistan, symptoms of post-traumatic stress hounded his daily life: flashbacks made it impossible to work and his depression was incapacitating. He had spent much of his fifteen-month deployment driving along dirt roads in Paktia province in eastern Afghanistan, looking

for IEDs (improvised explosive devices). Route clearance is one of the most dangerous missions for US troops on the ground – a quarter- inch turn to the wrong side of the road can mean death or mutilation. “With friends that have passed, that have been blown up over there, it’s just constantly with you,” he said.

His symptoms became so debilitating that he eventually admitted himself to a stay in a mental health institution, just a few weeks before he heard about EquiCenter. When he started working with the horses, the results were astounding.

“It has helped me immensely,” he said. By focusing on taking care of the animals, he was able to become better at taking care of himself. Over time he became more patient, more present with his fiancée and children. “It’s the horses – they did this. They did all of it,” he said.

Symbols of the ‘spirit of the west’

Like Americans, mustangs are mutts. And they tend to be runaways: the feral horses that roam free in the west are descended primarily from the escaped horses of 16th century Spanish conquistadores stuck in the Florida mud, combined with US cavalry horses who deserted during battle and horses kept by Indigenous peoples.

The result has been a sturdy horse, smaller than a thoroughbred, sometimes beautiful and sometimes mulish. But it’s not what the mustang looks like that matters; it’s what they have come to represent. They’re an idealized American in animal form: powerful, self-sufficient and free. After having been hunted to near extinction, mustangs were

finally deemed a protected animal in 1971, declared to be “living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West.”

In recent years, mustangs have become part of a thorny conservation problem.

As their population has soared in the last four decades, the government now spends millions of dollars annually managing the estimated 100,000 wild horses and burros on public land. The government’s primary – and frequently criticized – solution has been to round up thousands of mustangs each year, placing some on government pastures and others up for adoption. The adoptions often fail, however, after the would-be adopters realize that training a mustang is not a simple task.

EquiCenter has offered a small-scale but powerful solution: by having the veterans spend as long as several months training the horses before they are ready to be rehoused with permanent adopters, the adoptions are much more successful. Not all mustangs can be trained to the point of functioning exactly as a domestic horse, but milestones in their training include being caught, led, groomed and lunged. Many can be ridden, and one of the horses from this program has even gone on to compete in events; another has shown aptitude as a therapy horse.

![]() The horses are part of the Mission Mustang program, which brings veterans and wild mustangs together. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

The horses are part of the Mission Mustang program, which brings veterans and wild mustangs together. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

Located in the village of Honeoye Falls, the nonprofit EquiCenter sprawls over nearly 200 acres of rolling farmland and nature trails. It began in 2004 as a riding program for children with special needs, and it has since expanded into a hub of outdoor therapeutic programs: riding lessons, an organic farm whose 2,000-pound harvest went to a veterans’ shelter during the pandemic, a cooking program and an apiary.

The mustang program, which is strictly for veterans and first responders, began in 2018, with just four horses. It is free to participants; however, many of the veterans offer an hour of volunteer time in exchange, such as gardening or mucking out stalls.

Over the course of a recent June day, veterans filtered in and out of the paddocks. They all noted how just being on the grounds of EquiCenter was a soothing tonic. Wytrwa said he could feel his blood pressure drop every time he drove up the winding driveway.

Luann Van Peursem, a veteran who received the Air Force commendation medal for saving two men during a rocket attack in Iraq, described the peacefulness she felt as soon as she saw the acres of white fencing and the horses munching on grass. “Something comes over you,” she said. “From the minute you walked in or drove in, you felt like you were family.”

Van Peursem, 62, first started coming for riding lessons in 2014 when nightmares, flashbacks and depression were consuming her life. “Coming back from Iraq, you just don’t have a lot of trust in mankind, and you just kind of isolate,” she said. The riding lessons could turn her day around, she says, so she was curious when the facility began working with mustangs. On the day the first mustangs arrived, they all hid in a corner, jumping at any noise. She turned to another veteran and said: “Do you see that? That’s us. That’s PTS [post-traumatic stress].”

![]() Veteran Luann Van Peursem, 62. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

Veteran Luann Van Peursem, 62. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

Working with a frightened animal forces the veterans’ nervous behavior to shift in the opposite direction: Confidence and calm are necessary to put the horse at ease. “That connection lets your anxiety relax – because the horses feed off of you. If you’re tight, they’re going to be tight,” Van Peursem said. Her work with the horses has been so helpful that she went so far as to say, “I wouldn’t be alive without it.”

Van Peursem always had an affinity for horses, but many of the veterans who come to the program have no experience, and so they rely on an experienced horse trainer. Steve Stevens more than looks the part of a mustang trainer: He wears boots, a big buckle belt and a cowboy hat with a feather blessed by his mentor, the Indigenous horse trainer Sonny Jim, of Modoc heritage.

Stevens grew up steeped in cowboy culture – but not in the traditional way. His father was a Los Angeles talent agent for the big Western movie stars, such as Chuck Connors of the Rifleman television series in the 1950s. The younger Stevens fell in love with horses and started riding at age 8 in the Los Angeles area before eventually becoming a professional saddle bronco rider.

For 12 years, he traveled around the country riding bucking horses at rodeos. He estimates he’s ridden thousands and watched tens of thousands. This work gave him an appreciation for their physical ability – and also for how delicate communication between human and horse can be. “Every bad thing that could happen has happened to me,” he said. “I’ve been kicked, run over, bit, you name it.”

He also had another realization: “There was a much better living in teaching horses not to buck than riding horses that buck,” he said. Stevens started a training business in North Texas with his partner, now his wife. He began working with mustangs out of necessity: There was always someone who adopted a mustang they couldn’t train, and Stevens had experience working with wild horses after spending summers on Sonny Jim’s reservation in New Mexico.

Like many people I spoke to, Stevens was conflicted about the idea of keeping mustangs in captivity, while recognizing the reality that with or without EquiCenter, mustangs are already living in government corrals or on private farms in huge numbers (as many as 50,000 horses, according to recent estimates).

In 1971, when the federal government assumed the responsibility of managing the feral herds, there were just 17,000 mustangs remaining. That number has nearly sextupled. Attempts to sterilize the horses have been met with outcry and lawsuits from animal rights groups, so the Bureau of Land Management’s primary (and often controversial) solution has been to round up mustangs by the thousands, removing them from public lands.

The roundups, which the bureau calls “gathers,” happen something like this: Helicopters hover above a herd of mustangs while bureau staff watch from a rocky mesa. It can take hours – even days – for the helicopters and BLMcowboys to herd the horses toward a trap. In some of the states where mustangs roam – Nevada, Oklahoma, Idaho – there is nothing but rock and dust as far as the eye can see: one former BLM official described watching the horses coming from miles away.

Like something out of a western movie, the observers watch the horses thunder across the ground, chased by the helicopters towards a natural funnel such as a rock formation. Then, the bureau releases the “Judas horse”– a mustang that has been captured and trained for this very purpose.

![]() Wild mustangs rescued from Bureau of Land Management holding facilities. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

Wild mustangs rescued from Bureau of Land Management holding facilities. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

As herd animals, mustangs are looking for a leader, so when they see the Judas horse in the distance, they follow it into a corral. From there they are tagged, some sent to holding areas, others put up for adoption. The Bureau of Land Management’s adoption program has been plagued by problems since its inception several decades ago – and as recently as May 2021, a reporter at the New York Times discovered that some of the horses adopted out from the government eventually ended up at slaughter auctions. (The Bureau of Land Management declined to comment on this story.

The solution is not as simple as leaving the mustangs where they are. Mustangs have several million acres to call home, but that number is deceptive: much of that land is rocky and dry. More than half of all mustangs in the US are believed to be in Nevada, where some have died from starvation or dehydration. Add to that the interests of cattle

ranchers and sheep farmers who want to keep the land for grazing their own herds, and quarreling horse activists who disagree about methods such as sterilization, and the answer of what to do with the mustangs is not an easy one.

That is where programs like EquiCenter can step in and make a difference. “I think the tough part for me is once the mustangs are captive, we want to help them,” Stevens said. “With the mustangs, there’s so much responsibility, because we’re taking them from their home – the wild – and now, as a human, we’re saying: ‘you need to figure out what we want you to do.’ And I really take great pride and responsibility for that,” he said.

Stevens uses a method of training called natural horsemanship, which focuses on communicating with a horse via body language. In the wild, the herd leader directs theother horses using his body. Stevens teaches the veterans to do the same: using their posture, breath and movements to communicate with the horse. “Just stand there for a minute,” he’ll tell one of the veterans, or “Take a big breath in and out.”

Part of the magic of the process is that it forces the trainer to be fully present in the moment. Much of post-traumatic stress is about the past living in the present, haunting it, holding it captive. The focus needed to win the trust of a wild horse requires complete attention. By maintaining that intense focus, often in a way that is inexplicable, healing seems to happen over time.

Rita Thomas has experienced that healing firsthand. At 56, she has a bright smile and a survivor’s ability to crack jokes about even the darkest moments of her life. A veteran of the 82nd airborne division, Thomas survived a bad accident during a parachute jump that left her with chronic back and knee problems, post-traumatic stress and the dissolution of her marriage to a fellow veteran.

![]() Veteran Rita Thomas, 56, works with a wild mustang named Beacon. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

Veteran Rita Thomas, 56, works with a wild mustang named Beacon. Photograph: Victor J Blue/The Guardian

Where some people hide their traumas, Thomas puts them all on the table. Within an hour of meeting her, she told me about her struggles with homelessness, her post traumatic stress and her veteran father’s suicide.

She hasn’t always been that way. When she first met the horse she would eventually forge a close bond with, she was terrified. Closed in the ring with a muscular black male mustang with a diamond of white between his eyes, she thought she was going to throw up from fear. But while watching him out in the paddock, Thomas soon felt something else: empathy.

The horse huddled in the farthest patch of grass in a way that reminded Thomas of her own tendency to “freeze” when experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Thomas has Indigenous heritage, and she thought about how the mustang had left a community of horses just as she had left a thriving Indigenous community in North Carolina to move to New York. She remembers thinking: “He’s just like I am.”

After months of training, she became so close to him that she was able to reach over and pull off the identifying tag that the BLM had placed around his neck when he was first captured. This achievement won her the right to name the horse. She chose to call him Beacon. As a satellite communications operator in the military, she sent out signals to connect with the beacon. For her, the horse represents the same light and hope. “He brought me out of a dark place,” she says. Thomas is now living in an apartment she shares with her daughter, has secured work and is rekindling her interest in art. She even wants to write a children’s book about her story with Beacon.

In the ring on a cool morning, Thomas takes careful steps toward the horse with her hand outstretched and then repeats: a few steps forward, a couple back. After many minutes of slow, careful movement, she’s close enough to reach out and touch him. She strokes him between the eyes.

“As veterans, we really feel like we need to have some kind of purpose. Here, when I come to my sessions, for that half hour or hour that I’m working, I know there’s a purpose, and so I don’t even think about anything else,” Thomas said. “If I don’t have a purpose for getting up, I just want to stay in bed. I still feel that way, but I know I can’t.”

Thomas is finding her footing both inside and outside the ring. And Beacon’s future is not clear either: who will adopt him, when and why, are questions yet to be answered.

For now, they both have this: an hour of focused peace. When she sends Beacon back out to the paddock after training, he no longer runs to hide in the corner.